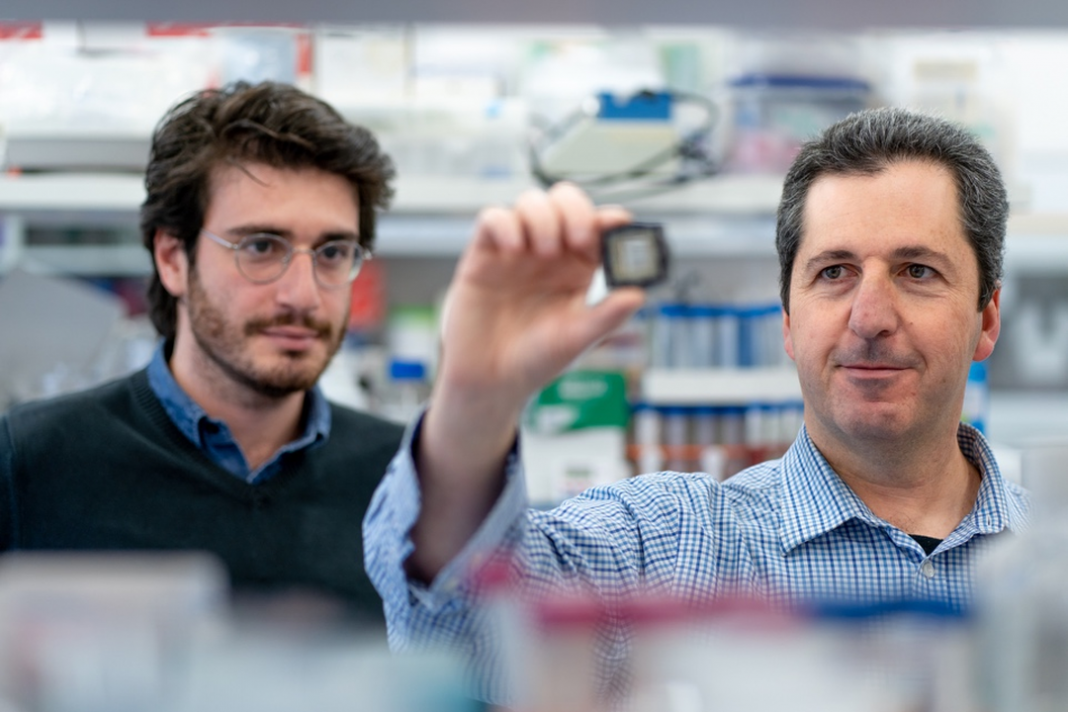

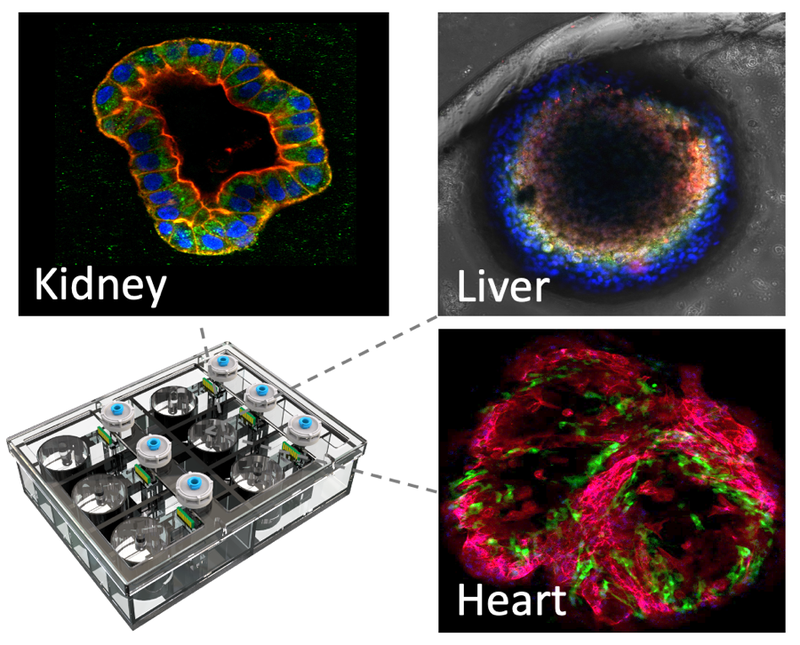

Israeli scientists have developed a cancer drug without testing it on animals by using a chip that simulates the human body. Hebrew University researchers created a chip containing human tissue with microscopic sensors to precisely monitor the response of the human body — kidney, liver and heart — to specific drug treatments.

The idea of organ-on-chip technology is 30 years old, but the Israeli team is believed to be the first to successfully create a new treatment using a chip’s capabilities in order to completely eliminate animal testing.

They are so confident in their research, which paired two existing drugs in order to solve a problem of excess liver fat experienced by some cancer patients, that they are submitting the combination for a patent, for clinical trials, and for approval by the US Food and Drug Administration — all while skipping the normal animal testing.

The success was reported in the latest edition of the peer-reviewed journal Science Translational Medicine. “To our knowledge this is the first time a drug is taking this step without animal testing, and the reason is that we have eliminated this need by using our ‘human on a chip’ technology,” Prof. Yaakov Nahmias, who is leading the research, told The Times of Israel.

“This is the first demonstration that we can use such technology to circumvent animal experiments, and this could lead to faster, safer and more effective drug development. Getting a drug to the point of clinical trials normally takes four to six years, hundreds of animals and costs millions of dollars. “We’ve done it in eight months, without a single animal, and at a fraction of the cost.”

He added that as chips have the potential to mimic the human body far more accurately than animals do, the technology could raise the accuracy of drug development. Nahmias, director of Hebrew University’s Grass Center for Bioengineering, set out to solve the problem that the commonly used cancer drug cisplatin causes a buildup of fat in human kidneys.

He added that as chips have the potential to mimic the human body far more accurately than animals do, the technology could raise the accuracy of drug development. Nahmias, director of Hebrew University’s Grass Center for Bioengineering, set out to solve the problem that the commonly used cancer drug cisplatin causes a buildup of fat in human kidneys.

He reported that when he “fed” cisplatin to his chip along with the diabetes drug empagliflozin, which is designed to limit the absorption of sugar in the kidneys, it became clear that the diabetes drug reduced the buildup of fat.

He looked to see if there was any real-world data that backed up his finding, and found that cancer patients receiving cisplatin who also take empagliflozin for diabetes are less prone to the buildup of fat in their kidneys.

This emerged as a clear pattern among 247 patients, he said. Nahmias likened his breakthrough to the development of the first self-diagnosing cars that report their problems and suggest solutions via a garage computer. “Today, we can easily tell if our car has a flat tire or an oil leak — our dashboard lights up because we placed sensors in all places that can go wrong in a car,” he said. “When our car fails, we simply connect it to a computer that can tell us what is wrong. Imagine doing the same thing, but for the human body. Suddenly this seems realistic.”