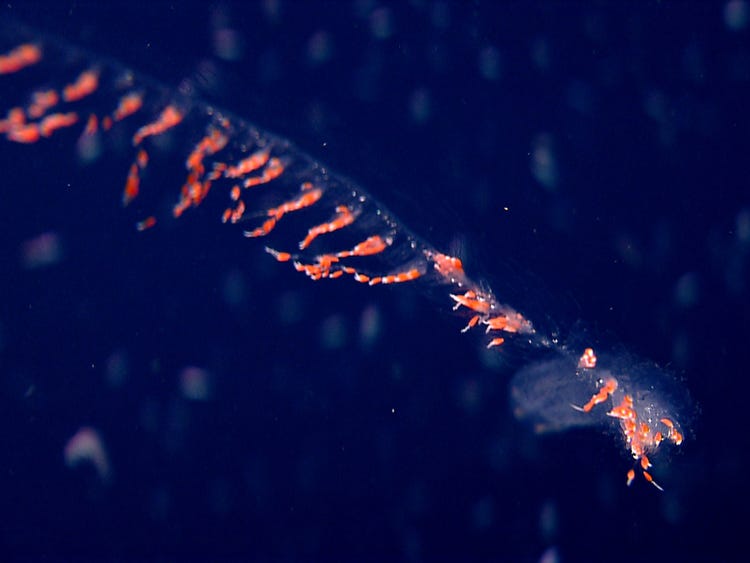

Nerida Wilson couldn’t take her eyes off the computer screen. Some 2,000 feet beneath the research boat she was aboard, a creature drifted past in the shape of a vast, galactic swirl. By her team’s estimates, it was 150 feet long.

“It looked like an incredible U.F.O.,” said Dr. Wilson, a senior research scientist at the Western Australian Museum.

She and her colleagues documented this organism with the help of SuBastian, a remotely piloted deep-sea robot, during a March expedition on the Falkor, a research vessel operated by the Schmidt Ocean Institute. Their mission was to understand what lives in the deep waters off Australia’s western edge. And the coiling stringy mass they had just found was a siphonophore, the first spotted off Western Australia and potentially the longest organism in the sea.

The longest previously known marine creature is the lion’s mane jellyfish — its tentacles can be up to 120 feet long. By comparison, blue whales, while the most massive creatures ever to have lived, are nearly 100 feet long.

Each siphonophore is a colony of individual zooids, clusters of cells that clone themselves thousands of times to produce an extended, stringlike body. While some of her colleagues compared the siphonophore to silly string, Dr. Wilson said the organism is much more organized than that.

The team aboard the Falkor captured 181 hours of footage during its trip, including the images of the spiraling siphonophore. The SuBastian underwater robot also brought back samples of deep-sea creatures living in Australian waters nearly 15,000 feet down, in Cape Range and Cloates Canyons.

“What’s fascinating about this particular part of the world is that it has not been explored,” said Jyotika Virmani, executive director of the Schmidt Ocean Institute. “Any time people go down into the deep sea, it’s so vast and yet so unexplored that it’s very easy to make new discoveries and to see something we’ve never seen before. It is like being on a new planet.”

Part of the goal of the expedition was to create a baseline understanding of the species there so that marine park rangers can know what they are protecting. In addition to samples and images, the scientists noted the temperature and pH levels of the water.

“Being able to characterize what is there in a changing climate is really important so that we know what we have and if we are losing anything,” said Carlie Wiener, director of marine communications at Schmidt.

In addition to the huge siphonophore, scientists aboard the Falkor identified up to 30 new species. They conducted visual surveys and collected samples of environmental DNA.

Georgia Nester, a researcher from Curtin University in Perth, Australia, filtered over 2,000 liters of water onto filter papers. Now back on land, she will extract the DNA from those samples and sequence it, to give scientists a snapshot of what creatures live in the area that they may not have seen.

Among the species they spotted were a large community of glass sponges in Cape Range Canyon. The sponges, mostly white or translucent, create their skeleton from silica fibers. “They can be in cross shapes or mushrooms or bobbles,” Dr. Wilson said. “Some look like a lollipop. Some are vases. Some are rolled hats. The analogies are endless.”

While they aren’t large, the glass sponges take decades to grow. “It’s like seeing an ancient forest, but a small, white one,” Dr. Wilson said. “You can see old perished colonies that are still attached but no longer alive.”

The team also saw a bioluminescent Taning’s octopus squid, which, while present in ocean basins around the world, had not been documented in Western Australia. “It wraps itself tightly and boops these little bioluminescent flashes and looks like it’s doing morse code,” Dr. Wilson said. “It had scars. It has lived a life.”

The scientists used a kitchen scrubbing brush attached to the deep-sea robot to take a DNA sample of the octopus squid. Preserved specimens of the species they collected will be exhibited at the Western Australian Museum.

“It’s just magic being there and sharing those things for the first time,” Dr. Wilson said.