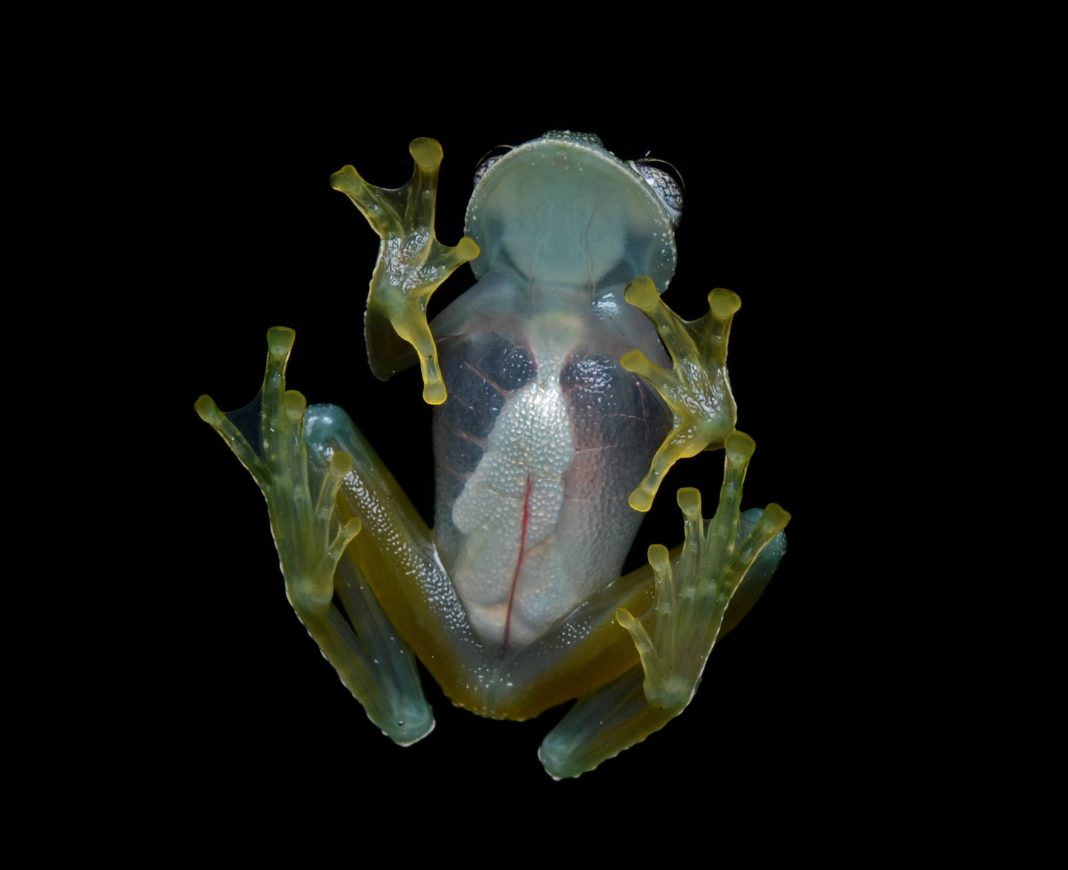

Two new species of glass frog were found living in the same 6,200-acre reserve, showing just how much is yet to be discovered in the tropical Andes.

At first, seeming perfectly identical to each other, the frogs were actually found to have very large differences on a genetic level, as well as different calls.

The newly-discovered hyalinobatrachium mashpi lives on the southern side of the Guayllabamba river valley, which separates its territory from that of another frog species, hyalinobatrachium nouns.

When biologist Juan M. Guayasamin and his companions entered the Guayllabamba area looking for species of glass frogs, they found several specimens that seemed to have all the same features.

They were both see-through, displaying their heart, liver, and GI-tract proudly through their translucent bellies.

Beyond that, they had the same speckled patterns on their lime-green backs, and the same miniscule size of two centimeters.

It was only back at the lab when Guayasamin and the rest of the research team were sequencing the DNA of the new frogs into the glass frog genetic database that they realized they were dealing with two totally unique species.

“What we are thinking is that the valley has kept these frogs from mixing with each other,” Guayasamin told National Geographic, noting that the two groups were found living merely 13 miles from one another. “When you have populations separated by a geographic barrier, you start having an accumulation of mutations in each group, and in time, they become genetically different.”

Northwest Ecuador is a place of such extraordinary biological diversity. It contains a South American biome known as the tropical Andes Mountains, which astonishingly contains twice as many amphibians as in the whole of the Amazon Rainforest. One of the reasons for this is that the Amazon Basin is actually rather flat.

A vertical world with numerous topographical barriers to the movement of species like the small glass frog, means the mountains offer far more isolation than the lowlands.

“The topography here is quite complex, with many unexplored niches and hard-to-reach areas, so endemism is very high,” an Ecuadorian herpetologist not involved with the discovery told Nat Geo.

Indeed, the total number of amphibians in the Amazon matches only the number of those specifically-endemic to the tropical Andes.

According to goodnewsnetwork.org. Source of photo: internet