The telescope, Baikal-GVD, is designed to search for neutrinos, which are nearly massless subatomic particles with no electrical charge. Neutrinos are everywhere, but they interact so weakly with the forces around them that they’re hugely challenging to detect.

That’s why scientists are looking under Lake Baikal, which, at 5,577 feet (1,700 meters) deep, is the deepest lake on Earth. Neutrino detectors are typically built underground to shield them from cosmic rays and other sources of interference. Clear freshwater and thick, protective ice cover make Lake Baikal an ideal place to search for neutrinos, researchers told the news service AFP on March 13.

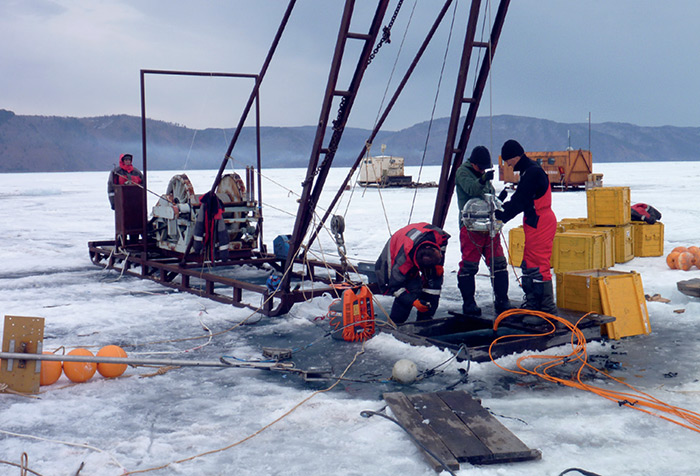

The scientists deployed the neutrino detector through the ice about 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) from the lakeshore in the southern part of the lake on March 13, lowering modules made of string, glass spheres and stainless steel up to 4,300 feet (1,310 m) into the water.

The glass spheres hold what are called photomultiplier tubes, which detect a particular kind of light that’s given off when a neutrino passes through a clear medium (in this case, lake water) at a speed faster than light travels through that same medium. This light is called Cherenkov light after one of its discoverers, Soviet physicist Pavel Cherenkov.

Researchers have been looking under Lake Baikal for neutrinos since 2003, but the new telescope is the biggest instrument deployed there so far. All told, the strings and modules measure about one-tenth of a cubic mile (or half a cubic kilometer), Dmitry Naumov of the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research told AFP. According to the scientific consortium that developed the telescope, it will also be used to search for dark matter and other exotic particles.

Baikal-GVD is about half the size of the largest neutrino detector on Earth, the IceCube South Pole Neutrino Observatory, which consists of the same type of light-sensing modules as Baikal-GVD, embedded in 0.2 cubic miles (1 cubic km) of Antarctic ice. IceCube detects about 275 neutrinos from Earth’s atmosphere each day, according to scientists on the project. The Russian scientists and their collaborators in the Czech Republic, Germany, Poland and Slovakia plan to expand Baikal-GVD to the size of IceCube or larger in the upcoming years.

According to livescience.com